What Time Is It?

As we (still) shelter in place, who cares?!

I have always struggled to be on time. Somehow, my natural tempo sends me to places either 10 minutes early or 5 minutes late, leaving me bored out of my skull (what can you actually do in 10 minutes?) or harried and flush with embarrassment. I have always assumed that this was my superpower (hey, superpowers can be bad — just because they’re not good doesn’t mean they’re not superpowers), and all I could do was fight to be the person that shows up annoyingly early every time. It was exhausting, and I never understood why others found it so effortless.

Then, the pandemic taught me that my bad superpower has a flip side, and in a situation like the one we are currently in, it’s a good superpower. And, like many superpowers, I got this one from my parents.

I grew up unschooled in an off-the-grid home in rural Maine, with a feminist mother who took flack for deciding to be a full-time mom and a self-employed dad who kept us safe and fed. Unschooling varies by household, but in ours it meant that we spent most of our time doing whatever we wanted. We read books, built unstable treehouses, roasted apples over an open fire, played in the swamp, went over rickety bicycle jumps we constructed out of half-rotten boards and a couple large rocks, etc. So our sense of time was thoroughly disconnected from what the rest of society called ‘time’ — because it was based upon the emergent rhythms of our activity.

The Williams kids, corralled momentarily for this photo in the late 1980s.

At the same time that we were throwing rotten apples at each other until we got bored and decided to go pick blueberries on the barrens because we wanted a snack, children our age were having their activities dictated by an external clock (we are doing Science now, but in a couple minutes a bell will ring and we’ll have three minutes to fully switch from doing Science to learning how to type, and no snacks because it’s not 11:32 a.m. yet, which is the Time For Food). In other words, we obeyed our interests and bodily desires — and, sometimes, our parents — while other children were being taught to obey the bell.

As we grew up, those children transitioned to obeying other proxies for society’s time: their watch, the machine for punching into work, the exact moment that the bus will pass your stop if you’re not there to catch it, the time their kids have to be at school or risk a tardy slip. I, on the other hand, grew up to be finally introduced to the fact that an invisible and intractable force was now running my life — and I always struggled to be on time.

Then, many years later, in graduate school, my friend and colleague Crystle Martin introduced me to Gell (1992). Gell “divided time up into what he termed A-series time, or standardized time as measured by a clock, and B-series time, or time that is run by the punctuation of activity” (Martin et al., 2012, p. 229). I remember thinking, “Hah — I grew up in B-series time!” Now, the pandemic has upended the structures I had developed in the A-series time of universities, and I’ve realized just how much I relied upon various proxies for time to stay productive.

At first, I couldn’t focus on anything, and all the little rituals and plans and ways of keeping myself working (most of which focused on where I was when) were useless. After all, while society as a broad structure is still running on A-series time, our individual lives are running on B-series time — with all the familiar A-series structures fallen by the wayside. No longer is there a place that indicates work (driving to the office signifies that it is Time to Work) — there is only this one place (home) that signifies everything, and thus nothing. And the nearest proxy for time — my computer clock — does not anchor me into the familiar pattern of a day. It’s 9:50 am eastern, and who cares?

So, I have let myself fall back into the soft fluffy B-series time of my childhood. Rituals and plans have drifted away. I haven’t worn my watch in weeks, and I ignore the little proxies for time sprinkled around my home. Instead, I have reverted to obeying my interests and bodily desires, just as I did as a barefoot, curious, creative kid. For those of us academics learning to work away from the Ivory Clocktower (brilliant phrase coined by the brilliant Ana Ndumu) and needing to learn (or re-learn) how to strive in unstructured, organic rhythms, I’ve outlined how I manage in this new B-series world.

First, I am fortunate enough that I have a job that I generally enjoy — so I have projects that are interesting and make me want to get right into B-series time and a sense of flow (e.g., Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2005). But even interesting projects have to be organized, so I have a Magic Method from the brilliant Susan Winter — but you have to promise to continue reading past the first sentence of the next paragraph, because it will make you snort in disbelief. (I know this to be true because the first time Susan Winter explained it to me, I snorted in disbelief. Then came back to her two months later and said, “I can’t stay organized — what should I do?!” And she explained it again, and I didn’t snort, and now I’m a firm believer.) So just give me a little time to properly explain before you dismiss the Method. Promise? Okay, here we go!

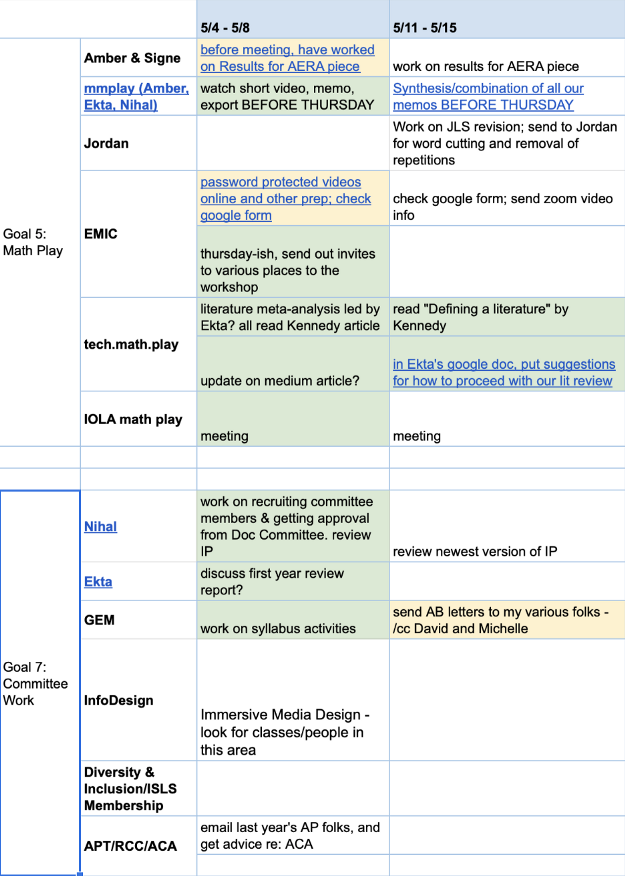

I use a Google spreadsheet. (Yep, let that snort out — get it over with!) Each column represents a week of time (proxies for time are useful, sometimes), and each row represents a different type of obligation, grouped within a meta-goal (e.g., Goal 6: teaching INST 728F). So today (a Tuesday), I had this week’s column to guide me, and then I had the beautiful luxury of choosing which project or obligation I want to work on right now — which activity should I punctuate my life with? Which makes me feel excited about jumping in and getting busy? Below are two of my meta-goals for this week and next — and you can see that there are obscure notes to myself alongside hyperlinks to make sure I have quick access to the most relevant digital information about that cell or row.

My spreadsheet: metagoals to the far left, subdivided into smaller obligations one column to the right of that, then weekly tasks for those obligations.

My spreadsheet: metagoals to the far left, subdivided into smaller obligations one column to the right of that, then weekly tasks for those obligations.

So within today (a Tuesday), I had the current week’s column to guide me: this is what I want to accomplish this week. And then I allowed myself the beautiful luxury of choosing which project or obligation I want to work on right now — which activity should I punctuate my life with? Which makes me feel excited about jumping in and getting busy? When I do some work on a cell (say, Project mmPlay for this week — memoing video data), I highlight the cell yellow to indicate I’ve done some of it. When I complete the task (memo the entire second video, and export memos to share with the research team), I highlight it green — and then I ignore it for the rest of the week!

I also have a couple of odd rows, like “One-Off Service” — if an editor asks me to review a journal article, I can go directly to that row and see if I have a spare cell to tuck it in. All the cells are full for the next two months? Welp, too bad, can’t review. There’s also a row called “Annoying Bits” where I put the administrative paperwork (like filling out the travel reimbursement paperwork that has stopped piling up but is still piled up). Committees sometimes share a row, but my doctoral students get their own– sometimes it just says “weekly meeting,” but other times it says “Don’t forget to read that draft BEFORE the meeting!”

Then, at the end of the week, I move over any task I’ve left incomplete to the next week’s column (or ignore it as ultimately unnecessary), and “hide” the column so that my new week is the most prominent column. And, just to add a dash of gamification, before I hide the old column, I count up the green cells — total number of tasks I completed that week, which tends to be between 12 and 20—and transfer that number of dollars into my bank account that is for FUN STUFF ONLY. If the slow accumulation of guilt-free money into a fun-only stash doesn’t motivate you, find something that does. Maybe 5 minutes of pleasure reading for each completed task, so you can store them up and finally dig into those cosy mysteries you’ve been putting off. Or 5 minutes of Netflix—I recommend Keeping Up Appearances for an oldie-but-goodie (completing six tasks gets you an episode!). Or 5 minutes of the peculiarly peaceful Animal Crossing. Whatever you choose, take pleasure in adding up your completed tasks each week, and using your thoroughly deserved awards regularly.

So each individual day of my week is guided by my spreadsheet, but driven by my immediate interest (and see the Footnote and image below) — and I can work on what I’m most interested in until B-series time bops me on the head and says, “Your stomach is growling! Punctuate this activity with the activity of eating!” Often, after such a call by my bodily functions, I realize that I’m tired of working on that project — so I scribble a few notes to remember where to pick up next time, color the cell in appropriately, and move on to something else I feel like doing. Or I bite the bullet and do one of those Annoying Bits, just to give my brain something different-feeling to focus on.

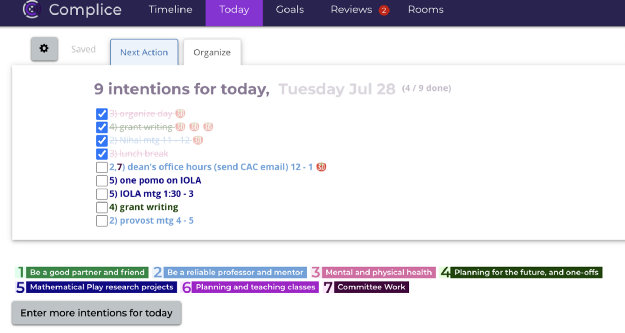

My Complice list for a single day — meetings and goals from my spreadsheet.

My Complice list for a single day — meetings and goals from my spreadsheet.

Now, here are is the single concession I make to A-series time: every single A-series time commitment I make (whether the weekly family zoom session, teaching my online class, a research meeting, a planned grocery trip, etc.) goes directly on my calendar, and I get alerts on my phone 10 minutes beforehand. (The school bell that kept kids on track in school, and reminded them that A-series time runs their lives, has now transitioned to a phone ding!) This way, I can otherwise ignore proxies for time, and I have 10 minutes to help myself transition from the interrupted B-series activity to the upcoming A-series one. That’s it — that’s all the A-series concessions I make. The rest of my life is B-series.

The world is a complicated mess right now — but accepting that my life is now B-series time has helped me ebb and flow with the new normal. Embrace motivation, interest, enjoyment, and necessities, and try a life that isn’t wrapped around your familiar proxy for A-series time. Give into the urge to do what you feel like doing, in the moment that you feel like doing it, and see what happens. It might just turn out that B-series time is your new favorite tempo.

…

Acknowledgements: Thanks to: Joan B. for helping me realize that my bad superpower had turned good; the fall semester’s students in my Games & Learning class for our discussion about A-series and B-series time; and my old research lab’s chapter Playing Together Separately (Martin et al., 2012) for getting my brain to mesh the two together. Additional thanks to Ana Ndumu and Jordan T. Thevenow-Harrison for their brilliant feedback on the original version, and to Mia Hinkle for her encouragement to dust this off and get it out there. #BlackTransLivesMatter

Footnote: As I’m looking over my spreadsheet each morning, and letting my interests guide me (or any hard deadlines for the day, like reading that integrated paper), I put the things that seem most interesting into my daily task list in Complice (www.complice.co). Complice was designed specifically to avoid stale task lists — that is, the constant accumulation of additional un-done tasks from day to day until your list is 3,007 individual tasks long and you decide to never look at it again. If you tend towards guilt-inducing stale tasks lists, try Complice — it complements the spreadsheet perfectly, because the spreadsheet gives you the long-term view and the weekly view, and Complice gives you the daily view (and some lovely co-working rooms!).

References

Gell, A. (1992). A-series:B-series::Gemeinschaft:Gesellschaft::Them:Us. The anthropology of time: Culture construction of temporal maps and images (pp. 286–293). Oxford: Berg.

Martin, C., Williams, C., Ochsner, A., Harris, S. King, E., Anton, G., Elmergreen, J. & Steinkuehler, C. (2012). Playing together separately: Mapping out literacy and social synchronicity. In G. Merchant, J. Gillen, J. Marsh & J. Davies (Eds.), Virtual literacies: Interactive spaces for children and young people (pp. 226–243). London: Routledge.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). Concept of Flow. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 89–105). New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.