Terp Magazine: Truth in Exile (ft. Richard Marciano)

Decades after more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were forced into camps during World War II, a UMD archival expert is making sure the dark history of their management finally comes to light.

Japanese Americans arrive by train to the Santa Anita Park assembly center in April 1942 before being sent to camps. More than 100,000 people were eventually imprisoned at locations in California, Idaho, Colorado and even Arkansas. (hoto courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library)

A FEW YEARS after Masao Kawate died in 1997, his son Haruo was sifting through his papers and diaries in Tokyo when a curious letter caught his attention.

Kawate, a high school teacher, had known that his father, a second-generation Japanese American born to immigrants in California, had lived in the United States before being imprisoned along with more than 100,000 other Japanese immigrants and Americans in camps during World War II. But the 1958 note addressed to a San Francisco attorney raised new questions about what that experience—and his father’s life—had actually entailed.

“I am now seriously thinking of going back to the United States if possible. But being a renounced I have to get my citizenship reinstated to do it,” he wrote. “In the past I have never filled out the affidavit to apply for reistating (sic) my citizenship because I thought my case was quite difficult. But having heard that many persons who were in the similar situation were successful in getting the citizenship reinstated through you, I have decided to write you.”

Kawate was baffled: Why did his father renounce his U.S. citizenship in the first place?

Masao Kawate and his family. (Photo courtesy of Haruo Kawate)

“Not even my mother knew this,” he told a documentary crew from NHK, Japan’s public media organization.

Kawate’s long search for answers eventually led him to the University of Maryland and Richard Marciano, a professor at the College of Information Studies.

It has been nearly a decade since Marciano first found largely unknown government files on internments. Working with his Advanced Information Collaboratory group, Marciano is building a new evidentiary infrastructure that will allow researchers, as well as survivors and descendants like Kawate, to access the hard documentation that remains—papers the government is allowing to be shared only now, more than 75 years after they were produced.

“These are really important records of daily struggles and what happened inside the camps,” Marciano says. “What’s hidden in the archives, what’s represented, the histories that are there are living histories and continue to be contested histories.”

FOR THE JAPANESE people first herded into racetracks and livestock pavilions in early 1942, and later camps scattered across California and Idaho and as far away as Colorado and even Arkansas, the official story that the government was trying to protect them from potential violence by their white neighbors evaporated quickly.

If that was the case, as historian Richard Reeves noted in his 2015 book “Infamy,” why were the machine guns on the towers pointed in toward them—and not facing out?

The road to those camps was built in earnest after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, but the racial animosity that laid the foundation started much earlier. Laws dating to the 18th and 19th centuries barred Japanese immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens, and new Asian arrivals were banned entirely in 1924. In 1940, all resident aliens, including nearly 92,000 Japanese, had to begin registering annually at post offices and notify the government of changes in address.

Within days of the strike in Honolulu, the FBI began arresting Japanese community leaders, and rumors spread of rampant sleeper agents just waiting for the emperor’s signal to sabotage American ports, naval bases and oil wells. Earl Warren, then California attorney general, said “that the Japanese situation as it exists in this state today, may well be the Achilles’ heel of the entire civil defense effort.”

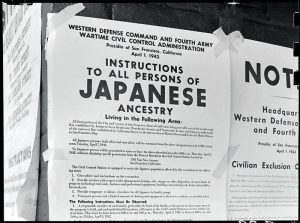

An April 1942 poster in San Francisco announces removal orders for Japanese immigrants and Americans. Spurred by racism and wartime paranoia, government and military officials were convinced this would solve a burgeoning national security issue during the early days of America’s involvement in World World II. (Photo via National Archives and Records Administration)

In February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 allowing civilians to be excluded from military areas, all-encompassing language that in practice was used to target West Coast Japanese. With often less than a day to prepare before an evacuation, families sold their farms and houses for pennies on the dollar and hastily stashed their possessions in warehouses, gave them away or unwillingly abandoned them.

Masao Kawate, then 28, had paid for his political science degree at the University of California, Berkeley by working as a farmhand. He still hoped to become a lawyer when he was loaded onto a bus at the Earl Fruit Company in Newcastle, Calif., on May 14, 1942, and taken more than 300 miles north to Tule Lake. In his diary, he described experiencing some initial relief in departing the suddenly hostile environs.

“Almost all evacuees were glad to leave their once-considered graveyard behind,” he wrote, “not because they wished for it, but because they were tired of living in uncertainty and insecurity.”

But as much as detainees tried to recreate life on the outside, with Boy Scout troop meetings, dances and baseball games, those efforts were superficial salves for crammed military-type barracks, open toilets and showers, and relentless cold, heat and wind. The suspicion, loneliness and isolation of people kept away from the rest of society for an indeterminate amount of time—despite being guilty of nothing—hung over everything.

“We were taught in school that we’re Americans. We had constitutional rights, civil rights, liberty, freedom, justice for all, and all of that gone. And yeah, I felt pretty angry about it,” Tom Akashi, who was imprisoned at Tule Lake as a teenager, recalled in a 2004 oral history. “I was the U.S. government’s prisoner for four years.”

Prisoners in the Tule Lake Relocation Center in California say goodbye to people being transferred and granted leave. Despite the stated security concerns, the growing need for military personnel and civilian workers eventually led to a declining camp population. (Photo via National Park Service)

The largest of the eventual 10 camps, Tule Lake provided the link between Marciano and the Kawates. In 2014, staff at the Tule Lake National Monument contacted the well-known archival and data visualization expert for help in getting more documents held by the National Archives. Of particular interest was anything that would shine more light on a handful of “incident cards” they had found that catalogued internal policing, ranging from lost property and dog bites to assault and even potential political crimes.

When Marciano went digging in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., he eventually discovered 25,000 of the yellowing, typewritten notes buried in faded blue boxes, the majority of them concerning prisoners at Tule Lake.

“They were police files, almost Stasi-like,” Marciano says, referencing the infamous internal security apparatus of communist East Germany. “It was about risk assessment.”

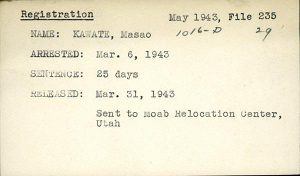

Among them was a card for Masao Kawate—“Arrested: Mar. 6, 1943”; “Sentence: 25 days”; “Released: Mar. 31, 1943”; “Sent to Moab Relocation Center, Utah”—and the key to an overlooked door in U.S. history.

THE INCARCERATION program quickly strained under the weight of its logistical and philosophical contradictions. As early as the aftermath of the June 1942 Battle of Midway, which crippled the Japanese fleet and its ability to reach American territory, the supposed tactical reason for the camps had largely disappeared. In addition, the need for military personnel with Japanese language skills, as well as civilians to work on the farms and in schools, hospitals and factories in the rest of the country, clashed with the alleged defensive policy of isolation.

Workers from the Tule Lake farm eat lunch. Tension over living and working conditions often led to protests and incidents catalogued on the archival cards discovered by UMD Professor Richard Marciano. (Photo via National Park Service)

In 1943, the population of the camps dropped from a peak of about 107,000 to 93,000 through resettlements, although wartime need and reintegration did little to soften the rest of America’s attitude. One poll of Los Angeles Times readers two years after Pearl Harbor found that 88% favored a constitutional amendment to deport everyone of Japanese descent.

Tension only increased following the administration of government loyalty questionnaires for internees 17 and older, asking if they were willing to serve in combat or auxiliary operations, and if they would swear allegiance to the United States and renounce any connection to the emperor of Japan. The latter question put everyone in a bind: For first-generation immigrants who could never become U.S. citizens, answering “yes” would render them stateless; for their children, it was offensive to assume that they had any allegiance to give up in the first place.

“I can’t seriously answer such ridiculous questions,” Masao Kawate wrote in his diary. “This is the greatest insult to us all.”

Masao Kawate’s incident card was among the files that UMD Professor Richard Marciano discovered in the National Archives and has been using to understand the internal security operations of Japanese camps during World War II. (Photo courtesy of Richard Marciano via National Archives)

That reaction turned out to be the basis of Masao’s incident card. In 2021, Marciano assisted Kawate in getting his father’s records from the National Archives and shared them with him and the producers of the 2022 NHK documentary; in addition, a team of Marciano’s students followed Masao’s archived paper trail and discovered that he was arrested for refusing to answer the loyalty questionnaire, spent time in penal colonies in Arizona as well as Moab before returning to Tule Lake, and even took part in protests over poor working conditions.

Akif Zaman ’23, an information science major who worked on that research with Marciano, says it was the first time he was part of a project where the data came across as collections of human experiences rather than just columns and rows of information.

“Sometimes we’d have to take a minute. It really takes a toll when you are sifting through pages and pages,” he says. “It made me question a lot of the things I have seen and was taught.”

As Allied forces continued to advance in the European and Pacific theaters in 1944, the federal government searched for a way to dissolve the internment camps. Some officials, such as Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, urged Roosevelt to just let everyone go—“the continued retention of these innocent people would be a blot upon the history of this country,” he told the president in a letter—but upcoming elections and the potential public furor following years of wartime propaganda argued against such an abrupt end.

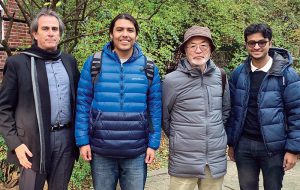

From left, UMD Professor Richard Marciano, Isaac Hernandez ’24, Haruo Kawate and Akif Zaman ’23 are pictured on campus. Hernandez and Zaman were part of a student team that researched the path of Kawate’s father in World War II-era Japanese camps. (Photo courtesy of Richard Marciano)

An alternate strategy emerged in a new law allowing Americans to renounce their citizenship in wartime. It not only gave camp authorities another tool to pressure people who didn’t want to stay imprisoned, but it also gave oxygen to nationalist gangs bullying their fellow prisoners to go back to Japan.

Masao’s status was particularly problematic to authorities as a “kibei” who had been born in the United States but spent years in Japan as a child before returning to American shores. One government document Marciano secured from the National Archives says that he could be a “definite menace to the internal welfare of the project.”

In the end, Masao—along with nearly 5,600 other Japanese Americans at Tule Lake—signed away his citizenship rights.

Haruo Kawate told NHK that he struggled to reconcile this aggrieved and resistant ex-American with memories of his father as a “mild-mannered and quiet person.” So he embarked on a 2021 U.S. road trip to retrace Masao’s journey and learn more about those experiences. One of his stops was in College Park, where he met with Marciano, Zaman and other students who had worked on the research.

He told Marciano, “The night I met you, I texted my wife and sister. My sister replied to me, ‘Our father is still alive in Maryland. I can’t stop my tears streaming my cheeks.’”

Article originally published in UMD’s Terp Magazine, February 3, 2023.