Building Community Through Coursework

Community engagement has become an increasingly important component of libraries and archives professions.

Eric Hung: Community engagement has become an increasingly important component of libraries and archives professions. Unfortunately, the skills needed for this work remains undervalued by many professional organizations and MLIS programs. Many information professionals struggle to start conversations when they table at farmers’ markets, facilitate conversations between the different communities they serve, and build successful partnerships with community organizations. These problems have led the Free Library of Philadelphia to hire a team of community organizers to strengthen community ties, develop new programming, assist with asset mapping, and train librarians in such skills as facilitation, coalition building, friendraising, and understanding relevance.

When I was hired to teach in UMD’s MLIS program, I decided to help my students develop these skills by incorporating a project with a community organization in each of my in-person classes. For my “Curation in Cultural Institutions” course in Fall 2019, we partnered with the DC-based 1882 Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to broadening “public awareness of the history and continuing significance of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.” The months since the beginning of the Coronavirus outbreak have unfortunately highlighted just how important this work currently is. If we compare anti-Asian propaganda from the 19th century to anti-Asian attacks today, we see the use of the same “yellow peril” tropes that emphasize disease, inscrutability, and perpetual foreignness.

The audience at the February 23 Talk Story at the I Street Conference Center.

Two of the 1882 Foundation’s key initiatives are the Talk Stories and the Symposiums. The monthly Talk Story series mixes lecture/discussions with scholars and artists with the telling of personal stories by community members. Meanwhile, the annual Symposiums are in-depth discussions of a “problem” that the 1882 Foundation is working to solve. The 2019 symposium, held at the Smithsonian Museum of American History, jointly celebrated the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Trans-Continental Railroad and developed strategies to preserve the area around the Summit Tunnel, the crowning achievement of Chinese railroad workers. Since Fall 2018, the 1882 Foundation has recorded these public events, and my class was tasked with creating a digital archive that will make these videos publicly accessible in an ethical and sustainable manner. Specifically, the 17 students and I collaboratively made decisions—in consultation with the Foundation—about the archives’ architecture, design, discovery tools, metadata and accessibility standards.

On February 23, 2020, we launched the 1882 Foundation Digital Archive at a Talk Story. Although more work needs to be done, we received very positive feedback from the audience and have seen links to specific pages shared on social media. The organization’s Executive Director, Ted Gong, also expressed his eagerness to continue collaborations with the iSchool. At this Talk Story, we combined the launch with a workshop that provided some basic tips on how descendants can best preserve family archives. Below, K. Sarah Ostrach, a student in the “Curation in Cultural Institutions” class, will talk more about the 1882 Archive, and Mea Lee, a student in my “Serving Information Needs” class, will discuss the effect that the workshop had on her father-in-law.

THE DIGITAL ARCHIVE

K. Sarah Ostrach: Working with the 1882 Foundation was an unparalleled experience in applying classroom concepts to a real-world project. Whether evaluating case studies or working together and with the Foundation to create their digital archive, we kept three questions in mind: Why are we doing this? Who benefits from this project? Who could be harmed by what we’re doing? Having a practical project drive the course made tangible these questions and the debates they engender. Understanding the mission of the Foundation, its participants, and its public was crucial to creating a digital archive that would adequately serve this community.

Ted Gong, the 1882 Foundation’s Executive Director, discusses how the Digital Archive relates to the next Symposium.

As a class we conceptually designed the archive and then built the digital environment in specialized teams. Conceptual decisions were made by consensus and negotiated between theoretical best practices and community needs. For example, the class found Library of Congress Subject Headings to be inadequate and culturally insensitive, and so we created our own standard vocabulary of subjects based loosely on an example from the South Asian American Digital Archive. This decision had pros and cons: finding language appropriate to the user community while sacrificing standardization across similar projects. In teams, we were responsible for creating the Front Page, Discovery Portal, Collection pages for the Talk Stories and Symposia, and a standardized Item page. I have such a greater appreciation for the communication involved, as each team had specifications to dictate to the rest of the class and required feedback or deliverables from other teams.

Individually, we all processed videos that would become the digital collection. Working with the videos was labor-intensive, requiring hours of transcription and learning new digital tools for editing video length and creating subtitles. We thus became intimately acquainted with the mission of the 1882 Foundation and its community members’ stories. For the public and unseasoned early career professionals, it is easy to underestimate the amount of unglamorous but critical work that goes into digital projects. Common challenges we faced were inaudible speech; adequately describing multiple speakers; unfamiliarity with place and people’s names in multiple Chinese dialects; and sensibly dividing long videos into series of shorter segments. We were also responsible for collecting and creating metadata for our videos that would be used to create the archive’s Discovery Portal and provide information on Item pages.

Evaluating case studies and doing an actual project for real people to whom you and your decisions are accountable are two very different ways of learning. We did both in Eric’s class and the two methods mutually informed each other. Having built a digital archive and experienced theory in practice, I feel more confident evaluating projects I encounter. Not only can I see the decisions other professionals have made, but I have a tangible understanding of how they were made. Presenting the archive to the 1882 Foundation community, receiving feedback, and having a conversation with the user community about moving forward further bolstered my confidence and commitment to serve as an information professional.

Evaluating case studies and doing an actual project for real people to whom you and your decisions are accountable are two very different ways of learning. We did both in Eric’s class and the two methods mutually informed each other. Having built a digital archive and experienced theory in practice, I feel more confident evaluating projects I encounter. Not only can I see the decisions other professionals have made, but I have a tangible understanding of how they were made. Presenting the archive to the 1882 Foundation community, receiving feedback, and having a conversation with the user community about moving forward further bolstered my confidence and commitment to serve as an information professional.

THE WORKSHOP

Mea Lee: During the workshop, I shared a story about my Father-In-Law, who immigrated from Taiwan. I felt his family story belonged in the archive because it affected the way I see the world and ultimately changed me for the better.

My Father-In-Law’s mother was born into one of the two most powerful families in Taipei. She was sent to Japan during the Japanese occupation to become a pharmacist. Meanwhile, the family decided to unite with the other most powerful family through marriage to increase their influence in Taiwanese society; this was an important strategy for protecting their wealth and power from the Japanese government. However, grandma secretly had a boyfriend and was against the family’s plans. The family forced her to return and locked her in her room until the day she’d marry. On her wedding day, the beautiful bride vowed that she would honor her family to get married and do the duties of an honorable married woman, but she would also drain her husband’s family’s glory and assets. Nobody believed her.

Mea Lee’s Grandmother-in-Law’s Wedding Photos.

In the following years, she raised three sons and one daughter to love and respect their mother even more than their father and worked on her wedding promise. Their assets and glory were slipping away due to their mother’s bad investments. By the time my Father-In-Law returned from a medical scholarship trip to Belgium, her work was almost complete. As first-born, my Father-In-Law had to make a choice; he could face and disgrace his mother, or he could ignore it. He chose to escape and moved to America for a medical residency.

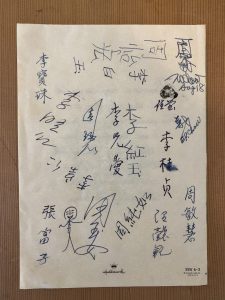

He met a stunning nurse while working in America, who had an adorable baby of her own. He sent wedding invitations to his family back in Taiwan. There were no answers for months, until finally a letter from his father, who had seen his wife’s struggle through arranged marriage, gave his blessing. His father sought family members to sign support for his oldest son’s marriage to a foreign woman whom he’d never met, but few signed the letter. His mother did not sign it.

The wedding card signed by Mea Lee’s grandfather-in-law and relatives; Mea Lee’s father-in-law and his wife.

My Father-In-Law worked hard to support and provide for his family. His job was not easy; perfecting English and dealing with racism were even harder. He tirelessly worked but along the way, he failed to build bonds with his American children or to make them understand his sacrifices for their happiness. He spoke nostalgically about his family’s old glory in Taiwan; at family gatherings, he repeated the stories again and again. His American family got bored and the purpose of the story was lost.

After his story was heard at this event, my Father-In-Law no longer repeats his Taiwanese family’s glory stories. His story was heard, and his family and audiences understood that he was a good father. This changed not only my father-in-law’s outlook; it changed all of us. We became warmer and more understanding by archiving our history. Every family holds many stories, but for immigrants, there are stories to be heard that can change you for the better.